We know that statistics (which is different from mathematics) plays an important role in various other sciences (mathematics is not a science, it’s an art). But still I would like to discuss one very interesting application to linguistics. Consider the following two excerpts from an article by Bob Holmes:

1. ….The researchers were able to mathematically predict the likely “mutation rate” for each word, based on its frequency. The most frequently used words, they predict, are likely to remain stable for over 10,000 years, making these cultural artifacts, or “memes”, more stable than some genes…..

2. ….The most frequently used verbs (such as “be”, “have”, “come”, “go” and “take”) remained irregular. The less often a verb is used, the more likely it was to have been regularised. Of the rarest verbs in their list, including “bide”, “delve”, “hew”, “snip” and “wreak”, 91% have regularised over the past 1200 years…….

The first paragraph refers to the work done by evolutionary biologist Mark Pagel and his colleagues at the University of Reading, UK. Also, “mathematically predicted” refers to the results of the statistical model analysing the frequency of use of words used to express 200 different meanings in 87 different languages. They found the more frequently the meaning is used in speech, the less change in the words used to express it.

The second paragraph refers to the work done by Erez Lieberman, Jean-Baptiste Michel and others at Harvard University, USA. All people in this group have mathematical training.

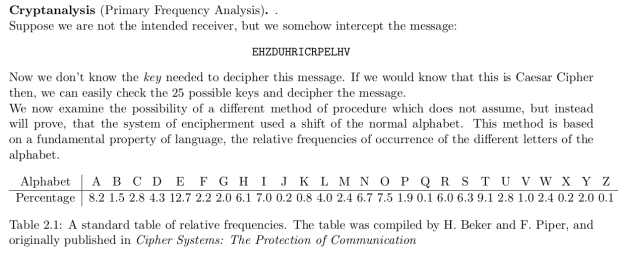

I found this article interesting since I never expected biologists and mathematicians spending time on understanding evolution of language and publishing the findings in Nature journal. But this reminds me of the frequency analysis technique used in cryptanalysis:

You must be logged in to post a comment.