I won’t be writing new blog posts here anymore.

All the past blog posts and static pages will be available in read-only format (i.e. no new comments can be made on this website).

I won’t be writing new blog posts here anymore.

All the past blog posts and static pages will be available in read-only format (i.e. no new comments can be made on this website).

In 1852, Chebyshev proved the Bertrand’s postulate:

For any integer

, there always exists at least one prime number

with

.

You can find Erdős’ elementary proof here. In this post I would like to discuss an application of this fantastic result, discovered by Hans-Egon Richert in 1948:

Every integer

can be expressed as a sum of distinct primes.

There are several proofs available in literature, but we will follow the short proof given by Richert himself (english translation has been taken from here and here):

Consider the set of prime integers where

. By Bertrand’s postulate we know that

.

Next, we observe that, any integer between 7 and 19 can be written as a sum of distinct first 5 prime integers :

7 = 5+2; 8 = 5+3; 9 = 7+2; 10 = 5+3+2; 11 = 11; 12 = 7+5; 13 = 11+2; 14 = 7+5+2; 15 = 7+5+3; 16 = 11+5; 17 = 7+5+3+2; 18 = 11+7; 19 = 11+5+3

Hence we fix ,

, and

to conclude that

.

Let, . Then by the above observation we know that the elements of

are the sum of distinct first

prime integers.

Moreover, if the elements of can be written as the sum of distinct first

prime integers, then the elements of

can also be written as the sum of distinct first

prime integers since

as a consequence of .

Hence inductively the result follows by considering , which contains all integers greater than

, and contains only elements which are distinct sums of primes.

Exercise: Use Bertrand’s postulate to generalize the statement proved earlier: If and

are natural numbers , then the sum

cannot be an integer.

[HINT: Look at the comment by Dan in the earlier post.]

References:

[0] Turner, C. (2015) A theorem of Richert. Math.SE profile: https://math.stackexchange.com/users/37268/sharkos

[1] Richert, H. E. (1950). Über Zerfällungen in ungleiche Primzahlen. (German). Mathematische Zeitschrift 52, pp. 342-343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230699

[2] Sierpiński,W. (1988). Elementary theory of numbers. North-Holland Mathematical Library 31, pp. 137-153.

About 2.5 years ago I had promised Joseph Nebus that I will write about the interplay between Bernoulli numbers and Riemann zeta function. In this post I will discuss a problem about finite harmonic sums which will illustrate the interplay.

Consider the Problem 1.37 from The Math Problems Notebook:

Let

be a set of natural numbers such that

, and

are not prime numbers. Show that

Since each is a composite number, we have

for some, not necessarily distinct, primes

and

. Next,

implies that

. Therefore we have:

Though it’s easy to show that , we desire to find the exact value of this sum. This is where it’s convinient to recognize that

. Since we know what are Bernoulli numbers, we can use the following formula for Riemann zeta-function:

There are many ways of proving this formula, but none of them is elementary.

Recall that , so for

we have

. Hence completing the proof

Remark: One can directly caculate the value of as done by Euler while solving the Basel problem (though at that time the notion of convergence itself was not well defined):

The Pleasures of Pi, E and Other Interesting Numbers by Y E O Adrian [Copyright © 2006 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.]

Dr. Jaydeep Majumder (07 June 1972 – 22 July 2009)

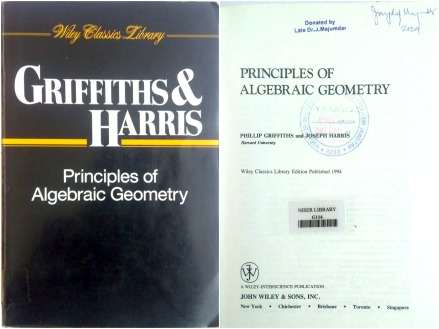

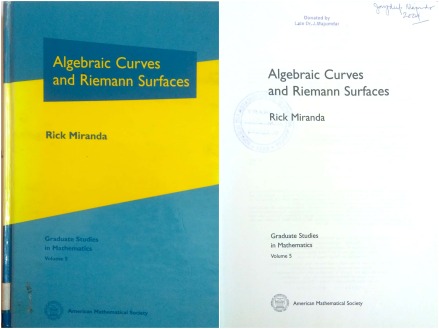

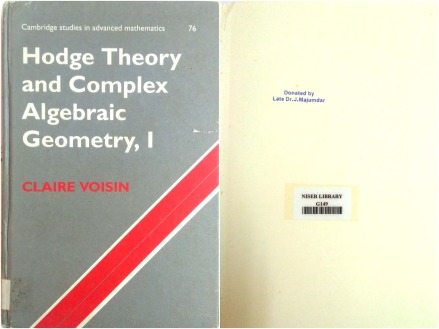

Recently I finished the first part of my master’s thesis related to (complex) algebraic geometry. There are not many (useful) books available on this topic, and most of them are very costly. In fact, my college library couldn’t buy enough copies of books in this topic. However, fortunately, Dr. Jaydeep Majumder‘s books were donated to the library and they will make my thesis possible:

Principles of Algebraic Geometry by Joseph Harris and Phillip Griffiths

Algebraic Curves and Riemann Surfaces by Rick Miranda

Hodge Theory ans Complex Algebraic Geometry – I by Claire Voisin

While reading the books, I assumed that that these books were donated after the death of some old geometer. But I was wrong. He was a young physicist, who barely spent a month at NISER. A heart breaking reason for the books essential for my thesis to exist in the college library.

Dr. Majumder was a theoretical high energy physicist who did research in String Theory. He obtained his Ph.D. under the supervision of Prof. Ashoke Sen at HRI. He joined NISER as Reader-F in June 2009, and was palnning to teach quantum mechanics during the coming semester. Unfortunately, on 22 July 2009 at the young age of 37 he suffered an untimely death due to brain tumor.

I just wanted to say that Dr. Majumder has been of great help even after his death. The knowldege and good deeds never die. I really wish he was still alive and we could discuss the amazing mathematics written in these books.

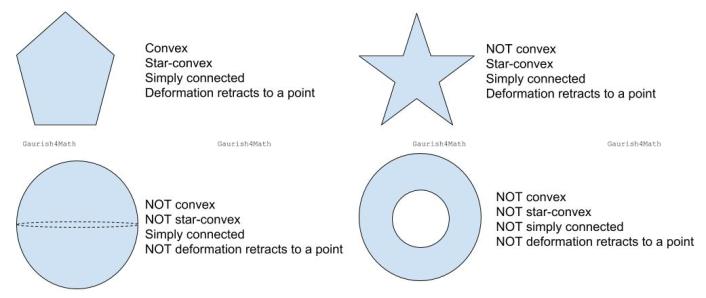

Following are some of the terms used in topology which have similar definition or literal English meanings:

Various examples to illustrate the interdependence of these terms. Shown here are pentagon, star, sphere, and annulus.

A stronger version of Jordan Curve Theorem, known as Jordan–Schoenflies theorem, implies that the interior of a simple polygon is always a simply-connected subset of the Euclidean plane. This statement becomes false in higher dimensions.

The n-dimensional sphere is simply connected if and only if

. Every star-convex subset of

is simply connected. A torus, the (elliptic) cylinder, the Möbius strip, the projective plane and the Klein bottle are NOT simply connected.

The boundary of the n-dimensional ball , that is, the

-sphere, is not a retract of the ball. Using this we can prove the Brouwer fixed-point theorem. However,

deformation retracts to a sphere

. Hence, though the sphere shown above doesn’t deformation retract to a point, it is a deformation retraction of

.

Following is the problem 2.16 in The Math Problems Notebook:

Prove that if

, then we do not have any nontrivial solutions of the equation

where

are rational functions. Solutions of the form

where

is a rational function and

are complex numbers satisfying

, are called trivial.

This problem is analogous to the Fermat’s Last Theorem (FLT) which states that for ,

has no nontrivial integer solutions.

The solution of this problem involves proof by contradiction:

Since any rational solution yields a complex polynomial solution, by clearing the denominators, it is sufficient to assume that is a polynomial solution such that

is minimal among all polynomial solutions, where

.

Assume also that are relatively prime. Hence we have

, i.e.

. Now using the simple factorization identity involving the roots of unity, we get:

where with

.

Since , we have

for

. Since the ring of complex polynomials has unique facotrization property, we must have

, where

are polynomials satisfying

.

Now consider the factors . Note that, since

, these elements belong to the 2-dimensional vector space generated by

over

. Hence these three elements are linearly dependent, i.e. there exists a vanishing linear combination with complex coefficients (not all zero) in these three elements. Thus there exist

so that

. We then set

, and observe that

.

Moreover, the polynomials for

and

since

. Thus contradicting the minimality of

, i.e. the minimal (degree) solution

didn’t exist. Hence no solution exists.

The above argument fails for proving the non-existence of integer solutions since two coprime integers don’t form a 2-dimensional vector space over .

These are the two lesser known number systems, with confusing names.

Hyperreal numbers originated from what we now call “non-standard analysis”. The system of hyperreal numbers is a way of treating infinite and infinitesimal quantities. The term “hyper-real” was introduced by Edwin Hewitt in 1948. In non-standard analysis the concept of continuity and differentiation is defined using infinitesimals, instead of the epsilon-delta methods. In 1960, Abraham Robinson showed that infinitesimals are precise, clear, and meaningful.

Following is a relevant Numberphile video:

Surreal numbers, on the other hand, is a fully developed number system which is more powerful than our real number system. They share many properties with the real numbers, including the usual arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division); as such, they also form an ordered field. The modern definition and construction of surreal numbers was given by John Horton Conway in 1970. The inspiration for these numbers came from the combinatorial game theory. Conway’s construction was introduced in Donald Knuth‘s 1974 book Surreal Numbers: How Two Ex-Students Turned on to Pure Mathematics and Found Total Happiness.

In his book, which takes the form of a dialogue, Knuth coined the term surreal numbers for what Conway had called simply numbers. This is the best source to learn about their construction. But the construction, though logical, is non-trivial. Conway later adopted Knuth’s term, and used surreals for analyzing games in his 1976 book On Numbers and Games.

Following is a relevant Numberphile video:

Many nice videos on similar topics can be found on PBS Infinite Series YouTube channel.

Consider the following polynomial equation [source: Berkeley Problems in Mathematics, problem 6.13.10]:

Let’s try to figure out the rational values of for which

is an integer. Clearly, if

then

is an integer. So let’s consider the case when

where

and

. Substituting this value of

we get:

Since, we conclude that

. Also it’s clear that

. Hence,

and we just need to find the possible values of

.

For we get:

Hence we have . Since

, we have

, that is,

.

Similarly, for we get

. Hence we conclude that the non-integer values of

which lead to integer output are:

for all

I read the term “number theory” for the first time in 2010, in this book (for RMO preparation):

This term didn’t make any sense to me then. More confusing was the entry in footer “Number of Theory”. At that time I didn’t have much access to internet to clarify the term, hence never read this chapter. I still like the term “arithmetic” rather than “number theory” (though both mean the same).

Yesterday, following article in newspaper caught my attention:

The usage of this term makes sense here!

Consider the following entry from my notebook (16-Feb-2014):

The Art Gallery Problem: An art gallery has the shape of a simple n-gon. Find the minimum number of watchmen needed to survey the building, no matter how complicated its shape. [Source: problem 25, chapter 2, Problem Solving Strategies, Arthur Engel]

Hint: Use triangulation and colouring. Not an easy problem, and in fact there is a book dedicated to the theme of this problem: Art Gallery Theorems and Algorithms by Joseph O’Rourke (see chapter one for detailed solution). No reflection involved.

Then we have a bit harder problem when we allow reflection (28-Feb-2017, Numberphile – Prof. Howard Masur):

The Illumination Problem: Can any room (need not be a polygon) with mirrored walls be always illuminated by a single point light source, allowing for the repeated reflection of light off the mirrored walls?

The answer is NO. Next obvious question is “What kind of dark regions are possible?”. This question has been answered for rational polygons.

This reminds me of the much simpler theorem from my notebook (13-Jan-2014):

The Carpets Theorem: Suppose that the floor of a room is completely covered by a collection of non-overlapping carpets. If we move one of the carpets, then the overlapping area is equal to the uncovered area of the floor. [Source: §2.6, Mathematical Olympiad Treasures, Titu Andreescu & Bogdan Enescu]

Why I mentioned this theorem? The animation of Numberphile video reminded me of carpets covering the floor.

And following is the problem which motivated me write this blog post (17-May-2018, PBS Infinite Series – Tai-Danae):

Secure Polygon Problem: Consider a n-gon with mirrored walls, with two points: a source point S and a target point T. If it is possible to place a third point B in the polygon such that any ray from the source S passes through this point B before hitting the target T, then the polygon is said to be secure. Is square a secure polygon?

The answer is YES. Moreover, the solution is amazing. Reminding me of the cross diagonal cover problem.

You must be logged in to post a comment.